Git: rebase vs. merge

We have all gotten acquainted with git in the last decade. We have adopted a way of working that has made it easy for all of us to work together in large teams and reduced the times our code changes collided to a minimum. When we do run into problems, they’ve culminated to a single important moment; the merge. We all know the merging feature of git with all its pro’s and con’s. But what about another feature of git: rebase?

What is rebase?

For those of you who are unfamiliar with rebase; rebase re-executes all commits of the current branch since its creation either on the parent branch again or on a different branch. In both cases the result of the rebase is a branch that is based on the head of the selected parent with all commits executed on top. This differs with merging, where the branch sprouts from a commit halfway down the parent branch and the recent changes of the parent are committed on top as the last commit.

Why rebase

The difference may seem semantic in nature, which has lead to a world where most of us developers stick only to merge as the result is the same for us. But in doing so, we blind ourselves to the broader use of our git repository, especially when working on complex, interwoven features.

Let’s go through a scenario where multiple developers will be working on the same feature. One of the developers will be working on some basic features that all the developers of this feature will need to build upon, but due to time constraints the work on the other features needs to start at the same time. A scenario that may seem all too familiar to some of you.

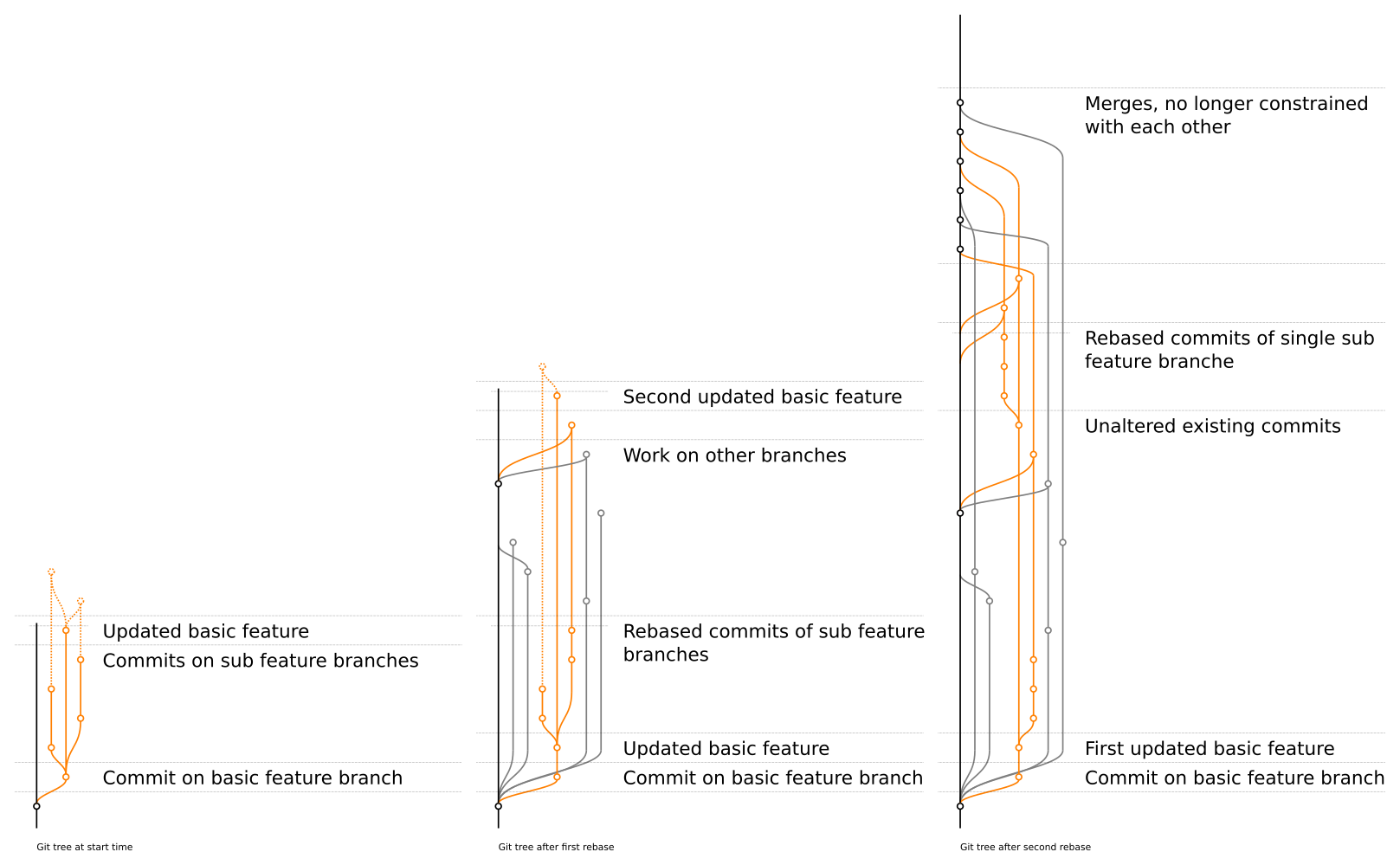

Every time one of the basic features becomes available, the other developers will pull the changes to their branches by merging the basic feature branch into their working branch. This may happen several times during development, potentially interspersed with merging changes from master as well to keep up to date with other developers working on unrelated features.

When the time comes to merge to master, we have a problem: our branches are contaminated. Many of the branches will now partially contain changes from the basic feature branch. If merged in the wrong order, or if basic features have been altered in the mean time in the basic feature branch, we run a high risk of introducing faulty code as we can no longer determine where the code came from.

If we were to use a re-basing strategy, we would still have the undesired effect of basic features becoming available while the branches relying on them are already in development, but by re-basing on the basic feature branch, the (sub) branches will always have all the basic features hierarchically before the first commit of their own branches. As such, there is only one commit containing the basic feature, instead of the basic features being introduced half way in a merge commit.

Now, when the time comes to merge to master, we have no contamination in our branches. The re-basing has made it so that the commits where the basic features were developed exist as a single chain of commits, with the branches that rely on them only branching off after the last of those commits. Regardless of the merging order, the basic features will always be merged once as git does not re-merge the same commit. There is no more cross contamination.

Keeping a clean git tree

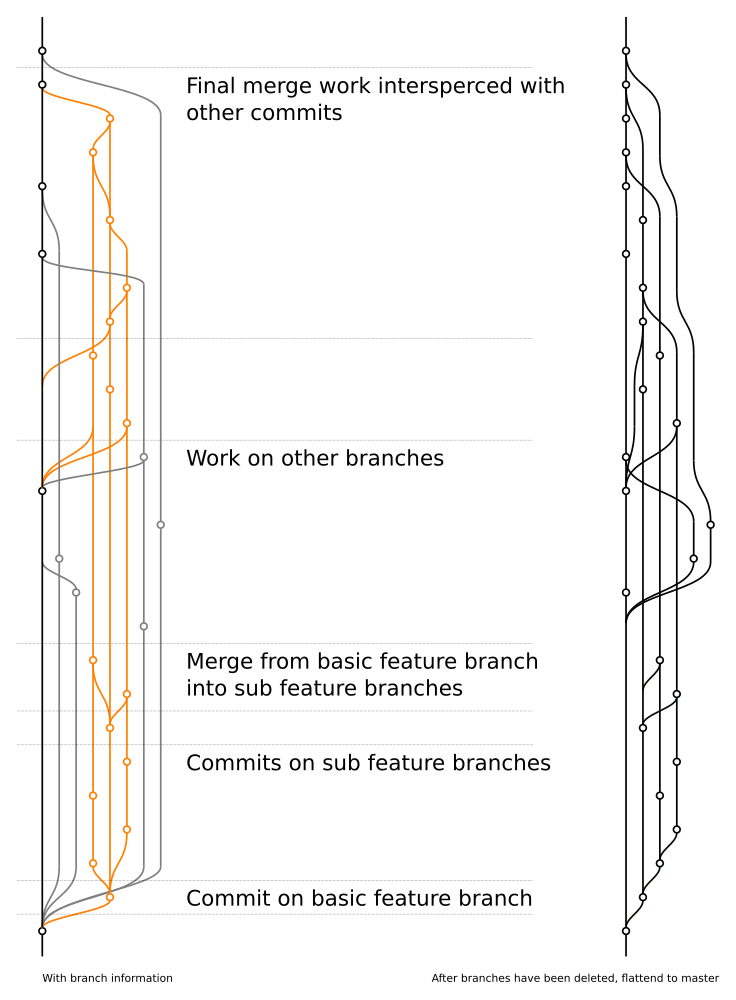

Re-basing has other benefits too, for example where digging into the history is required. When in the previous scenario, after some time as passed, we need to revisit the feature in the history to investigate some aspect of this feature, after the branches have been deleted, we find that it has become close to impossible to see the structure of the commits in relation to the development of the feature. Without this structure, finding out when something was introduced, why or what the context was for its introduction becomes diluted with influences from other branches that can no longer be tracked. With re-basing, as this removes all the merge commits from the hierarchy, removes the ambiguity from the commits, ensuring that they can be read as purposeful and singular without influences from other branches. This in turn allows for clear view on when, how and why some feature was introduced.

In conclusion

Before you decide to start re-basing instead of merging, re-basing is not a replacement for merging. Each has its benefits, pro’s and con’s. When to rebase and when to merge really depends on the situation. Sadly there are no definitive rules or guidelines to tell you exactly when to use one and when to use the other. This will be up to your own common sense.

There is, however, one scenario where it clearly has its benefits; the one used as example here. Whenever you or your team is working on features that rely on one or more features that are developed simultaneously, or if you have features that need to be released in another order than the order in which they are submitted, using rebase over merge is advised.

And, conversely, whenever you are working on an isolated feature that stands mostly on its own, continue to use merge.